Provenance

Prinknash Abbey, Gloucestershire

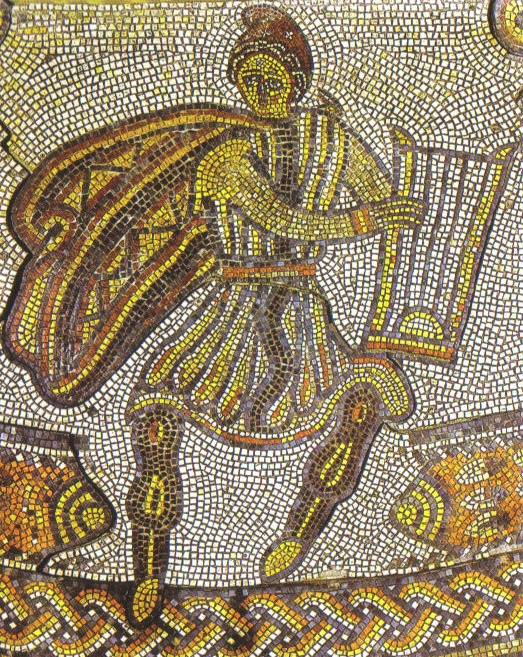

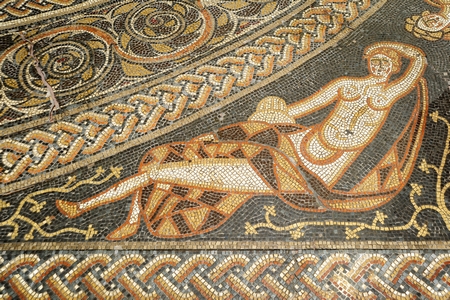

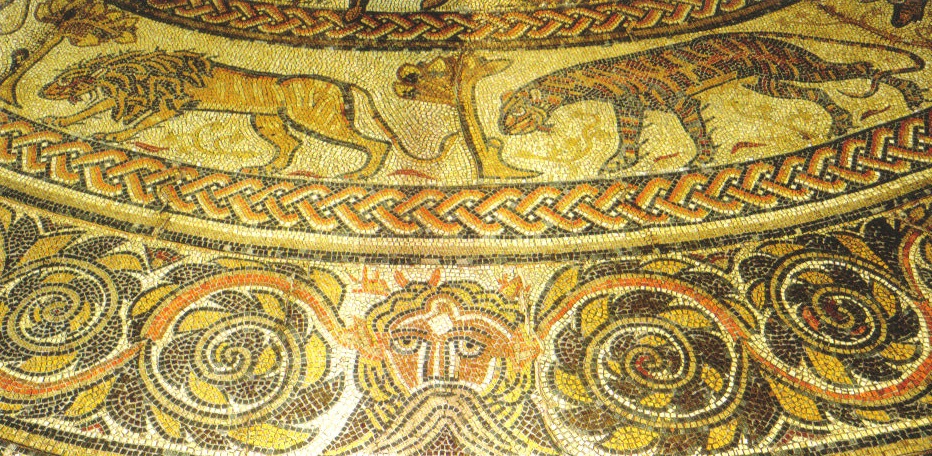

The Great Pavement of Woodchester is one of some fifty Roman mosaics depicting Orpheus charming wild creatures. These have been found in all parts of the Roman Empire and range in date from the second century to the fifth. The Great Pavement is believed to have been laid in around 325 A.D.. It is by far the most elaborate of the several hundred Roman pavements of decorative mosaic known in Britain and the largest in Europe, north of the Alps. The first recorded reference to this mosaic is in Gough’s ‘Additions to Camden’s Britannia’ published in 1695. This followed the visit to the site by Edward Lluyd, the Celtic scholar, two years earlier. In 1797 Samuel Lysons referred to the intricate mosaic as “The Great Pavement” and this name has been used in all published material since.

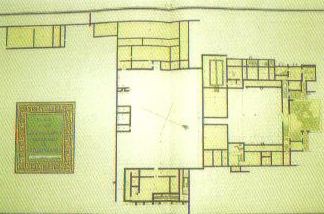

Several partial uncoverings took place before Samuel Lysons’ major excavations which culminated in his publication of ‘An Account of Roman Antiquities Discovered at Woodchester’ in 1797. The pavement was again fully exposed in 1880 in an attempt to rectify the numerous errors in the various plates that had been printed but unfortunately the 1880 plates also contained many inaccuracies. Further uncoverings for public viewing took place throughout the late 19th and early 20th Century and most recently in 1973, when the small village of Woodchester was swamped with over 140,000 visitors. It is estimated that approximately 60% of the original mosaic remains, the rest having been lost over the years through a combination of unsuspecting grave diggers and exposure to the elements. Since its last public opening in 1973, the pavement has been covered with a thick layer of soil and sand to protect it from further losses and currently there are no plans for any further public viewings.

The Woodwards had to confront two major challenges: firstly, to research the missing areas of The Great Pavement and to present the evidence of the many experts who were keenly interested in the subject and secondly to devise a method of constructing as near perfect a reproduction as possible. The first task was to make a comprehensive recording of the mosaic at Woodchester. In the days set aside for repair and consolidation of the vulnerable edges of the original work, after the public had been excluded from the site, the Reverend John Cull, Rector of Woodchester, gave permission for the brothers to have access to the mosaic. A commercial photographer was employed to photograph every section of the floor on a grid system.

In order to establish the content of the 40% of The Great Pavement that has long since disappeared from view, Bob Woodward spent several years undertaking thorough research at The British Museum, The British and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society and The Ashmolean Library among other institutions, and he worked closely with The Society of Antiquaries, the Association for the Study and Preservation on Roman Mosaics and The Royal Commission on Historic Monuments. He presented his findings to the Institute of Archaeology in the early 1980s and has received critical acclaim for the accuracy of his research.

When the time came to start the reconstruction, the Woodwards made a rough timber frame bench approximately 8’ x 3’, the top was covered with a sheet of armour-plated glass on top of which was placed a sheet of tracing paper. Two heavy commercial type projectors were mounted in steel frames and then placed into metal tracks within a trench under the bench. Using the colour transparencies of the original, a section of mosaic, approximately 6’ x 2’ 6”, could be shown onto the underside of a workbench, with tracing paper forming a screen for the projections.

Whilst recognizing that the Roman craftsmen at Woodchester had used local stone to make the Great Pavement, the difficulty of quarrying and cutting similar materials, with the additional problem of the weight involved, ruled out the use of natural stone for the project. Stone has of course evolved from clay and the most natural ‘substitute’ was to use clay to form the tesserae.

Tudor Potteries, located near Cardiff in South Wales, agreed to fire the strips of clay for the venture. Each of the colours used at Woodchester was cross matched with clay from various parts of the country. The most difficult stone to cross match with the Blue Lias and for this the pottery introduced suitable ‘body stains’. Twelve tons of clay were eventually fired, all approximately ⅜” thick and varying in width from ⅜” to 1 ¼”. Each strip was approximately 10” long. Piano wire cutters were used to cut each strip of clay into the tesserae. By using the glass topped bench and by shaping and laying each tesserae exactly on top of its counterpart on the projected image, the highest degree of accuracy was achieved.